Figure 1: Exploring underfoot. Being present in the moment. A mini community of natural beings working collectively in time. Photo taken Castlemaine, Dja Dja Wurrung Country, Victoria, 2018

Eco-Mythic Arts: A Reflective Journey on Art, Myth and Healing with the More than Human World.

This piece is part of a three-part reflective series on Eco-Mythic Arts

PART II: Art as Offering

In Part 1 of this series, we looked at the core foundations of eco-mythic arts as both a relational and regenerative practice. In this second part, I invite you to now turn from inside to out- towards community, culture and collective transformation.

As we live and practice eco-mythic arts, we begin to see its quiet potential to inspire change within our communities. In this way, creativity could be seen as the ember that sparks the beginning of transformation. This can be our offering.

As humans we often create art for ourselves, but eco-mythic arts can invite us to create as a form of collective action and a catalyst for cultural transformation. When we consider eco-mythic arts at both a grassroots community and collective level, we may be able to see its potential to create change. Eco-mythic arts creates space for people to share stories and feel what it is to be in reciprocal relationship – both human-to-human and human-more-than-human. It can also create more space for marginalised voices to be heard, as I believe we all have an innate connection to nature and a desire to belong. But it is more than this. Through careful interaction with our environments, eco-mythic arts can allow us to begin re-imagining public spaces as sites for creative an ecological restoration.

At a community level, collaborative murals on urban walls, events and performances honouring the seasons, and storytelling can bring embodied awareness and ritual into these spaces. Through these interactions, we can create deep, rich connections to our communities and the land we live upon (whether that be urban or rural). It can also potentially re-awaken a certain ecological consciousness in people who may not have felt this mythic current before. In this way, we can also begin to move beyond artmaking for self and invite the possibility of new cultural mythologies based on reverence and interdependence.

Many years ago, I co-created a large-scale labyrinth at the Seven Sisters Festival using natural and ephemeral materials, including sand, rice, pinecones, and flowers—this took two days to complete. This festival was a women's gathering in which attendees were invited into a space of collective healing, ritual, and reconnecting to land. Once this Labyrinth was complete, hundreds of women walked it over three days. This culminated in a special Saturday night ritual accompanied by live music from Wendy Rule and Kaisha.

Figure 2: A large-scale labyrinth created from sand and pinecones, Mount Martha - traditional lands of the Bunurong Peopla, 2016. This labyrinth was walked by hundreds of women- as a reclamation of who we are and how we belong , 2016.

This offering became more than an installation- it was a space for movement, intention, and mythic reweaving. This labyrinth became a moving ritual to land as well as community.- becoming a type of conduit for women to reconnect with land and with themselves. It opened up a space for people to be part of a living dialogue with the place, with other people and with story. In this way, it became a type of living myth under our feet and the ritual of walking through its twists and turns, an act of remembering and reforging. It became a reclamation of who we are and how we can belong.

Figure 3: Altar placed next to the Labyrinth at night-time as part of the ritual- including candles and sage and a group of people holding hands, 2016.

Art is an animating force. There is an energy to it that many people who have ever been part of its creation or even witnessed it in their day-to-day travels, may sense but not have the words to explain it. But when we think of this current, we can begin to understand perhaps how it contributes to the continuing transformation of social and ecological systems. Eco-mythic arts can also honour our ancestry and history and allow traditions to be brought forward to new generations. In this way, it becomes clear that eco-mythic arts is not solely about individual healing but also about the shared renewal of culture, land and relationship.

Healing with the More-than-Human World

In order to embed these cultural shifts in practice, we need to consider the intersection of creativity and ecology and how it can also transform us at an individual and therapeutic level. Personal healing and cultural renewal are not separate. Each one flows into the other, and through the lens of eco-mythic arts, this is where the boundary begins to blur. In a time of deep fragmentation, listening to place, honouring our grief and reclaiming forgotten stories can quietly start to restore our connection. When we create artworks within this conversation- with the land beneath our feet, with natural materials and with the deep mythic undercurrent- we are not only tending to our inner lives but also the broader fabric of culture.

We are invited to consider artmaking in a broader context when we look through an eco-mythic lens. Expressive arts therapies and artistic expression can help foster personal growth and healing. When we shift our perspective, we can also potentially see creative practice as a way to heal social and economic systems, histories and intergenerational narratives. Although art itself cannot repair systems and established patriarchal structures that we live in, it can become an essential part of helping us to heal our relationship with the more-than-human world collectively.

Figure 4: A co-created spiral made for a Winters Solstice Festival at Thornbury Primary School, Wurundjeri Country. Children and adults walked this spiral at night with beautifully created paper lanterns. Change can also begin within our school communities, 2016.

When considering the oppressive and colonial structures that do exist, this perspective calls for a decolonial lens. Many Indigenous traditions understand artmaking as a regenerative and relational force. One only needs to consider ‘songlines’ to recognise that story and art can sustain connections between people, places, ancestors and future generations. Engaging with these indigenous understandings requires humility, deep listening, and reciprocity.

The concept of Dadirri comes to mind, drawn from the Ngan'gikurunggurr and Ngen'giwumirri languages of the Aboriginal peoples of the Daly River region in the Northern Territory. As Elder Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann (2002) describes it:

"Dadirri is inner, deep listening and quiet, still awareness… it is something like what you call 'contemplation.'“

Figure 5: A photo of leaves with many colours and textures. The Grampians (Gariwerd) - home of the Djab Wurrung and Jardwadjali people, 2020.

What comes to mind when you think about this image?

This practice invites a state of receptive presence and a way of relating to the world that moves beyond thought and into a deeper somatic and spiritual attunement. Many of these cultural traditions have been fragmented by colonial systems, and to genuinely work within eco-mythic or relational frameworks, we must also acknowledge these histories and approach them with reverence, care as well as accountability. In my art-making practice, I sometimes actively explore how materials and sensory experiences can help me connect to my relational surroundings and the mythic undercurrent that I long to engage with more deeply.

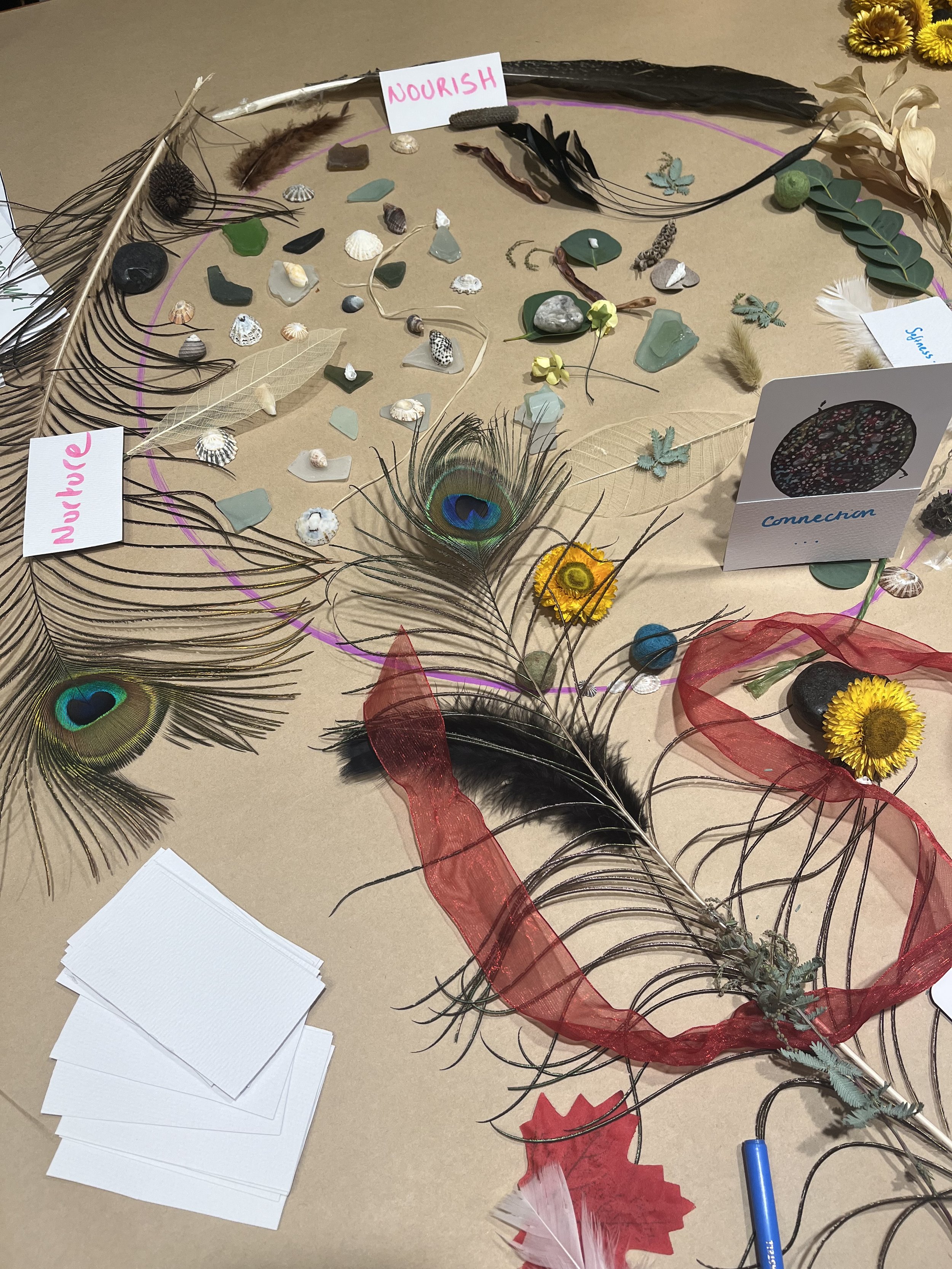

At the beginning of community-based and therapeutic group sessions, I often introduce natural materials. For example, stones, leaves, seeds, shells and feathers. I find offering these sensory and tactile objects (‘beings’ is perhaps a more apt term in the sense of this article) as an introductory point invites participants to attune to their embodied and emotional states and to express emotions and stories that have otherwise remained unshared.

Figure 6: As part of a six-week program for women – participants co-created a beautiful mandala with natural materials and found objects. Through its creation, themes of nourishment and connection emerged, 2022.

I have often observed how these tactile beginnings can lead to powerful and authentic sharing by participants. For instance, holding a stone or gently interacting with leaves and shells in a tactile way seems to encourage people to share their stories, memories and embodied sensations. From a transpersonal lens, I believe this interaction with natural materials can also invite archetypal insight and unconscious content into the space. Even at the most practical level, introducing materials like this can simply be a welcoming way to begin as it is easily accessible, tangible and non-threatening.

I have also found that sensory elements such as aromatic candles, herbs, and essential oils can deepen the embodied experience within individual sessions and group work. It has long been recognised that scents can awaken memories (even pre-verbal)– and I have found clients are often reminded of either someone in their lives or a place they remember – e.g. “my grandmother’s house” or the “lemon tree in my back garden as a child”. I have found adding sensory elements whilst working with older adults living with dementia is particularly well received and often elicits lively conversation. By adding sensory elements to a therapeutic session, we can invite participants to be more fully present and encourage stories that, again, may have remained hidden.

Eco-Mythic Arts in Practice

If we take the idea of eco-mythic engagement seriously, then art-making is no longer just about self-expression or even healing. It moves beyond the production of a finished object and instead invites a deeper inquiry:

How does creativity participate in the renewal of self, community and the broader animate and inanimate world?

How may I enter this mythic and ecological conversation through my own creative process?

I feel these are beautiful and important questions to ask ourselves, especially in an era when we are constantly inundated with stories of ecological and humanitarian crises. Creative practice, rooted in reverence and interconnection, can offer a space to respond differently and, in these responses - possibly be the ember that sparks the beginning of real change- rippling out into the world.

Reciprocity: Art as a Living Relationship

So, the invitation here would be to challenge ourselves to approach art as a living conversation and an unfolding relationship between human and the more-than-human world. In contemporary art making (even in therapeutic contexts), materials are are often used rather than truly engaged with. An eco-mythic approach invites a deeper shift- one that gently calls us toward co-inquiry and where the artist listens as much as they create.

In my blog post, Art Materials: Curiosity, Connection and Inspiration, I reflect on how our relationship with materials can open up a reciprocal dialogue between artist and the medium we hold in our hands. Relating to the materials in this way becomes an act of listening and reverence. Rather than imposing our own meaning onto the materials, we allow them to shape the artmaking process in collaboration with the artist

If we are wanting to be in genuine dialogue with our artmaking materials, we may:

• Source our materials with care whilst acknowledging their origins and histories

• Engage in place-based art that responds to specific landscapes and ecosystems- perhaps even tuning into the ‘energies’ of place.

• Recognise the individual agency of materials. For example, this may mean acknowledging that clay is malleable and wood is more rigid or that ink flows in a way that we may find hard to control.

Figure 7: A simple display of art materials—clay, pastels and tools. The way we engage with these materials influences how we create. It is always a reciprocal relationship, 2024.

Emergence: Working with Uncertainty and Change

Nature doesn’t work toward fixed outcomes. A forest doesn’t plan its regrowth after fire; it responds and adapts accordingly- often moving into new ways of expression. Similarly, eco-mythic art-making and healing do not necessarily follow a linear path. By practising in this way, we are invited to converse and create with the unknown, a space where change is not feared but welcomed through emergence and unfolding.

To nurture this way of art making, we can:

• Work with ephemeral materials such as ice, leaves or other organic materials that decay, deteriorate or transform.

• Consider external natural forces such as weather, gravity or decay as co-collaborators within the artmaking process.

• Allow and encourage collaborative community art-making to evolve emergently without having a static outcome in mind.

Figure 8: Engaging with natural elements in an embodied way can be a deeply rich experience. Collecting natural materials as part of the art-making process, Rerservoir- Wurundjeri Country, 2020.

Philosopher and storyteller Bayo Akomolafe once said, “the times are urgent, let us slow down”(2021). His words ask us as humans to lean into the complexity of our world, a world that keeps asking us to solve, to fix and feels like it wants us to know all the answers ‘right now’. His words invite us into a different type of tempo- one shaped by humility, relational presence and a certain willingness to not always know the outcome (or to arrive) but to stay with the becoming.

This orientation resonates deeply with the metaphor of the rhizome, which I explore in my blog post Rhizomic Musings: Finding the Unexpected in Art and Healing. In this blog, I reflect on how creative processes (like rhizomatic roots) often move unpredictably and can grow in unexpected directions. I find this way of working, of being with process rather than always needing to control it, often gives rise to the most surprising and transformative insights.

Figure 9: Lighting our way and slowing down. Jars with candles. Co-created labyrinth- Seven Sisters Festival, 2016.

In PART III, I invite you to join me as I explore how we can integrate eco-mythic arts into therapeutic practice and as a way of relational healing. I also invite you to consider how this living practice can provide us with a vital key- in reweaving our futures.

← Previous: Part I – The Roots of Eco-Mythic Arts

Next: Part III - Thresholds of Practice

Return to the full Eco-Mythic Arts series →

I would like to acknowledge Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann, Robin Wall Kimmerer, David Abram, Hannah Tuulikki, Andy Goldsworthy, Geoff Berry and Julie Lacy for their continued inspiration. As artists, thinkers, healers and writers, they are the change-makers the world needs right now- particularly in the fields of ecology, art, philosophical thinking and wellbeing. Through them, I continue to be inspired to view the world with eyes that are more open to possibility. For more inspiration, go to Kindred Voices

References:

Chayne, K (2021, July 19). Bayo Akomolafe: Slowing down and surrendering human centrality (No. 317) [Audio podcast episode]. In Green Dreamer: Seeding change towards collective healing, sustainability, regeneration. Green Dreamer. https://www.greendreamer.com/podcast/dr-bayo-akomolafe-the-emergence-network

Ungunmerr-Baumann, M.-R. (2002). To be listened to in her teaching: Dadirri. In J. Bentley & D. M. Habel (Eds.), Reconciliation: Searching for Australia’s soul (pp. 13–18). ATF Press. Retrieved from Dadirri- A Reflection, https://www.miriamrosefoundation.org.au/about-dadirri/