Figure 1: A symbolic, sand-based artwork integrating natural materials, figurines and candles- created during a self-exploration.

Eco-Mythic Arts: A Reflective Journey on Art, Myth and Healing with the More than Human World.

This piece is part of a three-part reflective series on Eco-Mythic Arts

PART III: Thresholds of Practice

This is the threshold where everything we have spoken about in this series, myth, ritual, and land-based creativity, crosses into the therapeutic space. Here, we consider some of the more practical applications of eco-mythic arts within therapeutic settings, including some gentle ways to engage with art and ritual as a form of ecological and relational healing.

Thresholds are spaces just on the edge of ‘stepping into’ something new. It is here that we can choose what to carry forward and how to integrate this into our practices- as humans, artists and as arts therapists

Integrating Eco-Mythic Practice into Therapeutic Work

Whether we are involved in artistic practice or therapeutic work (or both), it is vital to remain open to the unknown. Arts Therapy in a 1:1 capacity is a wonderful modality that supports people in their personal healing journeys, often offering new insights and the potential for growth.

But what if we extended these healing principles beyond the individual and into the broader field of ecological interbeing?

When we consider arts therapy within this context, we are again invited to consider that healing may also emerge through connection with the more-than-human world. It has become increasingly clear that nature-based modalities, such as forest or horticultural therapy, can offer powerful psychological and physiological benefits from being in contact with the natural world. While these are powerful modalities, eco-mythic practice combined with expressive arts invites us to go deeper into myth and story, as well as with creative reciprocity with the land.

In my own practice, I sometimes work intuitively with natural materials, and over the years have created ephemeral mandalas, sculptural nests and site-specific installations in open landscapes. These are spontaneous, embodied acts of making, yet they offer a visceral and mythic way of engaging with impermanence, reciprocity and renewal. They feel like small gestures of remembering- personal but important rituals of belonging to the more-than-human world.

What shifts when we co-create with the land, rather than simply based upon it?

Figure 2: This natural art installation was created at Fairfield Community Garden, Wurundjeri Country, during Spring. It highlights how something made by a human hand can be made in conversation with the landscape and impacted by seasonal changes, 2016.

Practices at the Threshold:

Within an eco-mythic arts framework, we can consider how we, our clients, as well as our communities, can explore this new territory in relatively simple and accessible ways:

Important note for working in the field: Honouring and respecting the landscapes is important as we collect and source nature-based materials. Please do not remove more than needed and never leave anything plastic or man-made behind. Always be respectful of animals and plants. This is about reciprocity and renewal, not exploitation and continuous extraction.

Materials as Co-creators

When we choose to work with materials, we are inviting them into a conversation. Every material has a different story if only we would listen to what it has to tell us as it rests in our hands.

Introduce natural materials at the beginning of individual and group sessions.

Consider artmaking as an ever-evolving conversation with the more-than-human world

Use natural materials such as stones, leaves, shells and flowers. Try to use them in new and innovative ways. E.g. sticks as paintbrushes, shells in sculpture and making ink from charcoal

When using materials, natural or not so natural … consider how they are also co-creators and collaborators in the art-making process.

Creating ink from charcoal, gum Arabic, and water is a straightforward process that can deeply connect clients to the materials they are using.

Create impermanent artworks within natural landscapes. Acknowledge that these can change over time through natural processes of decay and decomposition.

Weaving with natural thread and wool as a way to heal. Weaving is also lovely to do with others as it encourages conversation as we weave.

Figure 3: Weaving by Edwardes Park Lakes. Days spent with a dear friend who has since passed- weaving in thread and weaving conversations with words, Reservoir, Wurundjeri Country, 2020

During COVID 2020 (as part of my Masters in Therapeutic Arts Practice -MIECAT), I spent significant time with a dear friend, who has since passed, weaving down by a lake in a nearby suburb as a way for me to support her to build her artistic practice. We intentionally collected natural materials such as reeds and leaves from the surrounding landscape and then sat in quiet conversation and contemplation while we wove these materials into both physical form and rich story.

Figure 4: Paintbrushes made from sticks to use for markmaking on paper. In this Art and Wellbeing workshop, we also used charcoal to create ink with Gum Arabic, 2025

Sensory Integration and Nervous System Regulation

Every smell, texture, and sound has the potential to evoke memories or emotions from a past era or elicit new ones. They can also be very grounding as they bring us into the present moment.

Use natural scents, textures and sounds within sessions (e.g., mixing paint with essential oils, incorporating fabrics such as wool, or playing nature soundscapes in the background or as part of the artmaking process

Mindfulness can help regulate our nervous systems. This may mean walking barefoot on the ground or sharing locally sourced herbal tea like lemon verbena or chamomile.

Create soundscapes either inside or outside. Sound can offer an anchoring presence. Tuning into what is around us in an auditory way can bring us into the moment, whether that be a tram rumbling by, a bird outside the window or the gentle ticking of a clock.

Compile eco-journals from natural materials. As we collect different leaves, textures and found objects, these journals can also act as an anchor for grounding. This can also invite slow, embodied reflections that we can track over time.

Figure 5: Printing with fruit and vegetables on calico. A rich sensory and engaging process for older people living with dementia. Many commented on texture and scent- mint and lemon, zucchini and apple, 2024.

Working with older adults living with dementia, I have often incorporated natural materials into our sessions. In one group session- we used slices from fruit and vegetables to make beautiful prints on calico fabric. This raised lively conversations about gardening, family recipes and seasons- as well as it would seem a resonating dislike for ‘Okra’ though agreeing that it can make a beautiful star shape when printed. I have found that printing with leaves, as well as incorporating different scented oil helps stimulate memories as well as encouraging conversation

Honouring Seasons, Cycles and Land

When we honour the seasonal changes and cycles throughout the year, we can also begin to honour the changes and cycles within ourselves.

Honour Indigenous culture- by inviting clients and participants to know the name of the land that they live upon, e.g., Naarm (Melbourne) on Wurundjeri Country

Honour or explore the seasonal and lunar cycles. E.g. reflect upon seasons in ways that may highlight the cycle, times of hibernation (winter) and times of growth (spring) and how this may also be reflected in our inner states.

Celebrate or mark seasonal shifts throughout the year. This can be done through simple creative rituals and artmaking processes- such as creating a solstice altar out of natural objects or journaling about what may be being shed or is growing.

Take time to consider and reflect upon the Indigenous seasonal calendars in the respective lands that we live upon. These often hold deeper ecological rhythms and understandings than the four-season model we often refer to,

Notice what plants, animals and weather patterns are changing. These observations can become useful creative or therapeutic prompts for further exploration, eg, What are you noticing changing in your landscape? What season do you feel your body is in right now?

Creative Acts of Resistance and Renewal

Creating art in urban landscapes is a quiet form of resistance. Art can remind us that regeneration is possible and that big things can grow from the smallest of seeds.

Leave nature-based offerings within urban spaces. This may even invite resistance to the dominant paradigms, showing that there is a wild possibility in even the most unlikely places. For example, a ‘seed bomb’ left on a nature strip might flourish into wildflowers.

Build sculptures together and then actively dismantle them as a form of ritual. This could also be explored as a symbolic healing, transformation or release act. What are you building in your life right now? How would it look if it were dismantled? What has been built/created, and what would you like to unbuild/uncreate?

Consider how art can inspire new ways of thinking, especially if we put the art we have created out into the public domain- or as part of a public space.

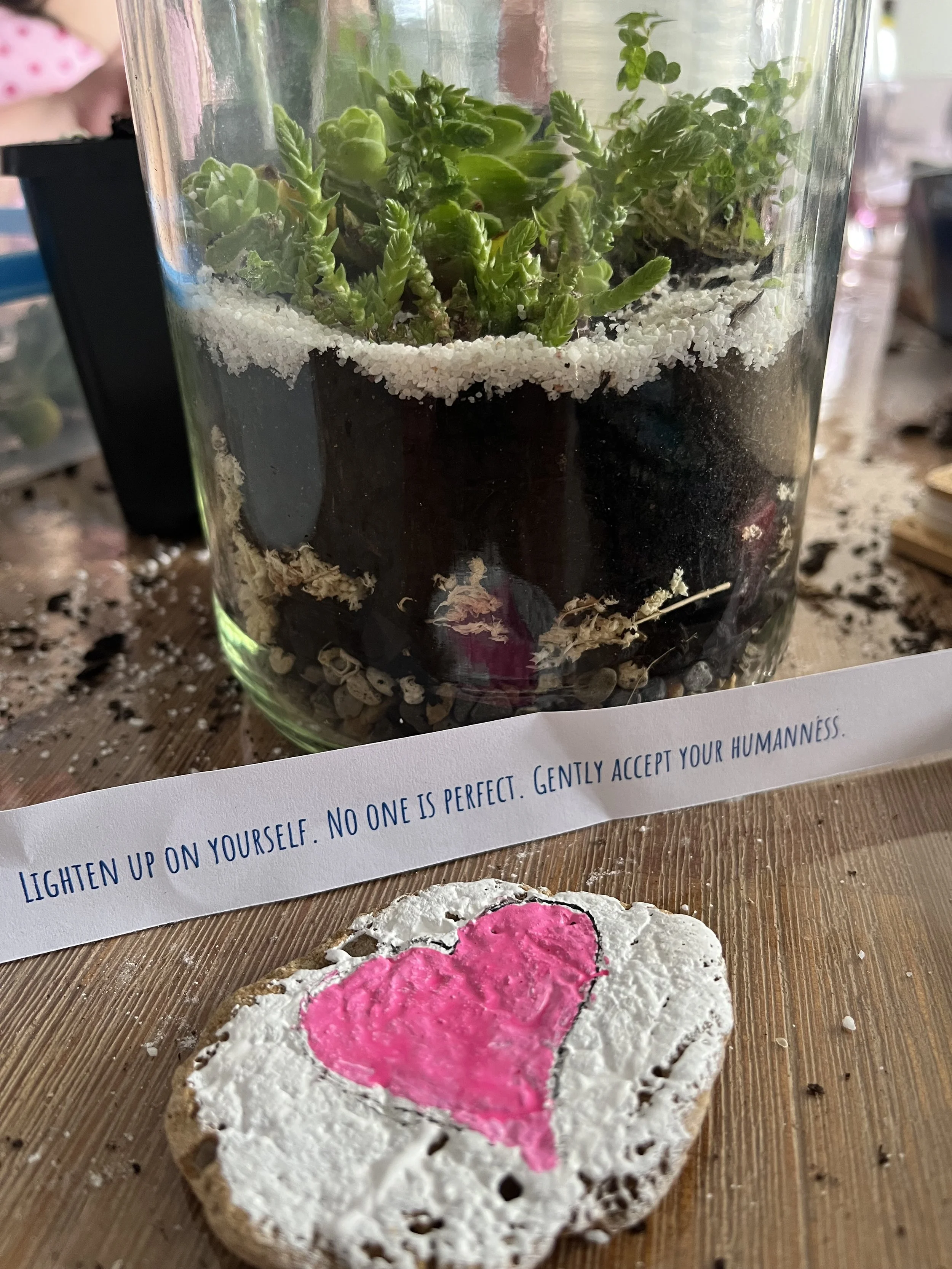

Figure 6. ‘Lighten up on yourself. No one is perfect. Gently acknowledge your humaneness’ (Deborah Day). This seems an apt choice of quote/affirmation when considering self-care. This was a layered and rich workshop that invited connection with the living world as well as with ‘self’, 2023.

In a session that I facilitated for a group of women and non-binary people navigating trauma and marginalisation, we created terrariums as a reminder of looking after ourselves with care. Participants co-created with soil, rocks, moss and ferns and shaped their own miniature worlds- then added small stones that they decorated with personal symbolic meanings.

As participants took part in this process, I noticed that they did so with a certain reverence as they interacted with the materials in their hands. I also hoped this process could remind us that we are still able to have a connection with the living world, even within our living rooms and urban surrounds. Since this session, I have heard more than one participant how well their terrariums are thriving at home and how lovely it is to have something ‘green’ to look at.

Language and Storytelling

Storytelling can be a way we can connect with all that is around us in a type of reverent spell- a way of unearthing the myth that resides beneath the moment, or the myth that resides within the river, tree or tide.

Introduce nature and eco-therapeutic journaling.

Write letters or poetry to trees or offer reflections on paper about rivers, oceans and the seasons. This can combine ecological reverence with myth and language.

Compose a poem from the perspective of an object or from the landscape. For example, “If I were the river- what may I say to the rock?”

Using natural materials such as stones and seedpods, create symbolic altars as storyscapes. These can be a launchpad for creating new stories.

Create urban shrines- an extension of symbolic altars these can be created in public spaces to encourage conversation and curiosity.

Some Final Thoughts: Art as Mythic Dialogue and Living Practice

Figure 7: A community-built sculpture of a woman sleeping made from dirt, mud, and ceramics. I took this photo in 2012 at a community day, but I cannot recall where. Please let me know if you recognise this sculptural creation so I can properly attribute it.

Eco-mythic arts asks us to move beyond the idea that art is inanimate and that artistic expression is purely individual. It calls us into a living dialogue with the more-than-human world that honours ecosystems, renews culture and remembers ancestral ways of knowing. Practising with eco-mythic arts is a practice of reciprocity. It is an act of attunement and helps renew our relationship to place, materials and the landscapes we live in. By embracing impermanence and the power of co-creation, we can begin to recognise that art (like nature) is always becoming as we are constantly changing, transforming and evolving.

This feels increasingly important right now, as the world continues to face ecological crises, social upheaval and cultural disconnection. As a practice, eco-mythic arts gives us the opportunity to be part of something that may help us to radically re-imagine what is possible in the way we live as individuals as well as collectively.

As we move beyond the self and begin to create in a relational process with the world around us, we can begin to heal our relationships with the more-than-human world and ourselves. Creativity offers us the opportunity to not only process our grief for the ecological devastation we live in but also gives us a chance to reweave our futures – so that they become more about thriving than surviving.

More and more in my own art practice and how I relate to the world daily, I also hear a quiet calling to engage more deeply with the mythical, the imaginal and the liminal. I feel increasingly compelled to explore more about creative practice and how it interconnects with ecological meaning as well as the world’s mythic undercurrents. I am also drawn more into the thresholds of the in-between- the space between concrete and everyday reality and that more mythic space. I am beginning to understand that this mythic space that resides somewhere beneath my thinking mind and within my body is where creativity is sparked and begins to flow through me and out into the world.

Where regeneration asks us to consider how creativity might sustain life, eco-mythic arts seem to invite some other questions gently:

How does creativity bridge the seen and the unseen?

What does it mean to create in conversation with nature myth, and memory?

Where do ritual, art and embodied storytelling meet in acts of living participation?

These questions invite me into a wilder and more expansive terrain. For me this is one where art is not only about regeneration but also about thresholds. Somehow, it feels like a return to something older and deeper, something that I know lives deep in the marrow of my bones. I believe it becomes a way of reaching closer to the ancient, toward that mysterious thread of the 'unknown' which is woven into the fabric of both land and story.

Figure 8: An afternoon of ritual and artmaking. My spiritual sisters and I marked our friend’s impending birth with painted henna markings and symbols on her beautiful pregnant belly and decorated the central table with natural materials and symbolic foods, Wurundjeri Country, Spring, 2018

As this series comes to a close, I hope it has sparked some new ways of thinking about creativity, connection and our relationship with the more-than-human world. Eco-mythic arts is not a fixed process; it is a living, evolving practice and one that invites deeper listening and creative responsibility. Thank you for journeying through these reflections. May they offer something meaningful for you as you walk your own path through art, myth and the more-than-human world.

You can follow my creative explorations at www.liminalwilds.com.au

← Previous: Part II – Art as Offering

Return to the full Eco-Mythic Arts series →

Acknowledgment of Influences

My interest in the relational world and eco-mythic arts has stemmed from many years of involvement in environmental and community initiatives and my continued love of myth, storytelling, visual arts and dance. This series has grown through many seasons of reflection and embodied experiences with the natural world. It has also been inspired and influenced by the practices and voices of writers, artists, thinkers and healers who also walk the eco-mythic terrain. I offer them deep gratitude:

David Abram

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Resmaa Menakem

Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann

Geoff Berry

Julie Lacy

Bayo Akomolafe

Andy Goldsworthy

Hannah Tuulikki

Figure 9. My son collecting natural materials to create a sculptural ‘nest’ for Easter Bunny to leave his/her eggs in. When we combine tradition and land-based creativity, there is always a possibility to approach things differently, Hobart (Nipaluna) - traditional lands of the Muwinina People, 2013.